On Patents, Applications and Prior Art

The recent bizarre behavior of Information Architects with their app, Writer Pro, generated a good deal of new discussion about an old subject — patents. Instead of focusing on the distasteful behavior, I’ll try to draw some value from this affair and use the Information Architects' patent applications to illustrate various aspects of the patent process. I’ll specifically focus in on the limitations for the public submission of prior art against patent applications.

Some Back Story

Oliver Reichenstein of Information Architects made some veiled threats on Twitter about a patent application for “Syntax Control”, one of the functions in their app Writer Pro.

(Link to Tweet on December 19, 2013)

This was the spark for much scorn from the indie development community. However, it was just the beginning.

The initial Tweet was followed by a blog post that (previously) stated: “If you want it in your text editor, you can get a license from us. It’s going to be a fair deal”. This language has since been revised.

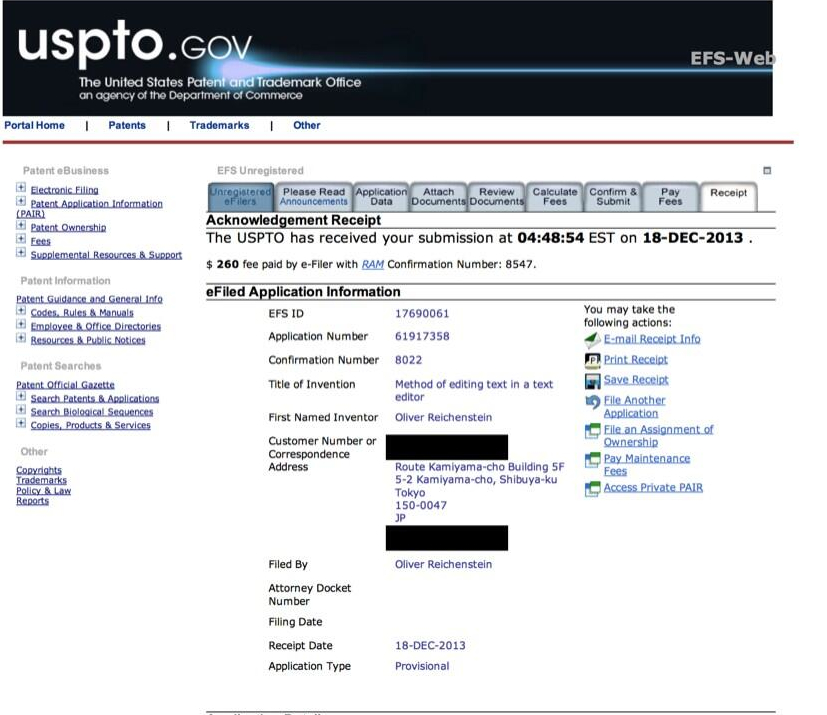

Subsequently, Reichenstein brandished a screen capture of the patent application in a Tweet which has now been deleted. I preserved the original image (redactions are not mine):

After considerable backlash, iA raised the white flag:

(Link to Tweet on December 24, 2013)

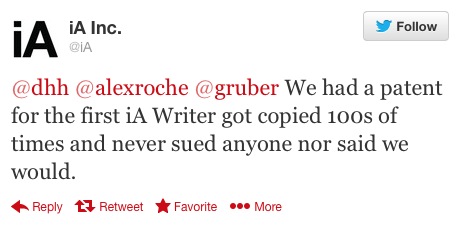

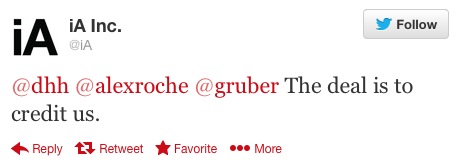

Several days later, an iA representative stated the following on Twitter:

(Link to Tweet on December 27, 2013)

It is worthwhile examining the realities of patents and patent applications in the context of this type of behavior. I will state unequivocally that this article is not a take down of iA patents, because iA and Oliver Reichenstein DO NOT OWN A PATENT OF ANY KIND.1

The Real Story is About Patents

I’d like to take a deep dive on a subject that is poorly understood yet incredibly important in this age of unprecedented technological development.

As I was reminded on Twitter, Stack Exchange’s Ask Patents provides a valuable service to the layman.. It details the process for submitting prior art against a patent application.

It’s important to only submit art that seems likely to be relevant to the application that it predates. (If you’re not sure, ask a new question about the relevance here on Ask Patents.) The goal is to make a meaningful contribution to the patent process, not spam a patent examiner’s inbox.

This seems simple enough, but it really is just a narrow window on a much more complicated and time consuming process. I thought it would be more valuable to focus on this aspect of patent applications2 than to just add more blind criticism on top of iA. However, in doing so, I think I end up highlighting some of the serious, yet common, mistakes that Reichenstein and iA made while adding fuel to their own pyre.

On Patents

I have mixed feelings about patents.3 Their primary intent is to provide motivation for inventing novel solutions to problems. In theory, granting market exclusivity for a limited period of time mitigates the risk associated with research and development. Reduced risk to research should mean more innovation, which overall benefits society.

Our current patent system is suffering from the growth of non-practicing entities, also known as “patent trolls.” These warts on the system extract their own monetary value without providing any real benefit through their own research and invention. Their blight is so detrimental, that Congress has begun to take action to help stave off the negative impacts on the US economy and innovation.

The rise of software patent trolls has also muddied the water around the layman’s concept of novelty. I’ve read enough confused opinions about novelty, patent applications and prior art that I wanted to understand the entire process better.

There are two prongs to be overcome in order to warrant the temporary4 exclusivity provided by a patent: proving your invention is novel and proving your invention is non-obvious.

Novelty

Novelty is asserting that your unique invention is not known to the public as you describe it. It’s important to understand that “novel” does not mean “non-obvious”, the second criteria for being granted a patent. If you think novelty is easy to define, you’d probably be wrong. History is littered with examples of disputes over novelty, such as the 1892 dispute over patent rights for barbed wire. It comes down to a relatively easy measurement: is the new invention exactly the same as a previous invention. If not, then it can be considered novel.

However, an invention will not typically be novel (and not patentable) if the invention was known to the public before it was “invented” by the individual seeking patent protection. This means that if you used the invention publicly, presented it in a publication or offered it for sale to the public prior to the filing date, then it is not going to be considered novel.

Novelty can be very narrowly defined and in my opinion is typically a low hurdle to overcome. If the invention, as described, is different from previous inventions in some way, then it is probably going to pass the test.

Luckily, novelty isn’t the only barrier for a patent application. Non-obviousness is also required for an invention to be patented in the US.

Non-Obviousness

The second hurdle for any successful patent application is non-obviousness.5 This is traditionally a difficult barrier for an applicant. The criteria for obviousness is clearly documented by the USPTO and derived from many decades of Supreme Court rulings. However, courts have repeatedly reaffirmed the obviousness criteria. Non-obviousness is asserting that your invention is not a common sense addition to what is already known to the public.

When a work is available in one field of endeavor, design incentives and other market forces can prompt variations of it, either in the same field or a different one. If a person of ordinary skill can implement a predictable variation, § 103 likely bars its patentability. For the same reason, if a technique has been used to improve one device, and a person of ordinary skill in the art would recognize that it would improve similar devices in the same way, using the technique is obvious unless its actual application is beyond his or her skill.

As recently as 2007, in KSR v.s. Teleflex, the Court further defined obviousness:

In determining whether the subject matter of a patent claim is obvious, neither the particular motivation nor the avowed purpose of the patentee controls. What matters is the objective reach of the claim. If the claim extends to what is obvious, it is invalid under § 103. One of the ways in which a patent’s subject matter can be proved obvious is by noting that there existed at the time of invention a known problem for which there was an obvious solution encompassed by the patent’s claims.

Let me distill this down to something digestible. The Supreme Court ruled that when determining obviousness, a court (or USPTO) can evaluate whether a knowledgeable person may have reason to extrapolate to a claimed invention, thus making it obvious and ineligible for patent protection. This ruling was substantial and immediately impactful with many USPTO rejections since 2007 citing the KSR case. Prior to KSR, courts narrowly evaluated whether there were teachings on the specific problem that would directly predict an invention.

Obviousness is very often confused for novelty by the layman. In reality, when attempting to invalidate a patent (or application) the approach should include examining both aspects.

Public Prior Art Submissions

Prior art is anything that was publicly known before a specific date that might be relevant to an application’s claims of novelty and obviousness. Prior to March 2013, the specific date would have been the date of the original invention or idea. However, the US followed the rest of the planet and switched from First to Invent to First to File. The rule went into effect in March 2013. For patent applications since the rule change, the “specific date” is the application filing date.

While old, this IP Watchdog article has a good summary, and there is one important take home point:

The reality is that there is always prior art for an invention, the questions are just how close is it to what you want to protect and what are the reasonable expectations for obtaining a patent? That is why inventors should always do their own patent search to start, but should also eventually hire a patent attorney to engage in a thorough patent search and patentability assessment.

This is one reason why “good” patents are expensive. It’s also why the public input period is important. Patent applicants have a duty to disclose to the USPTO any prior art they are aware of that is material to patentability, meaning anything that an examiner would find relevant in determining whether or not to grant a patent. However, this disclosure is not made when an application is first filed as a provisional application.

If an applicant is aware of relevant prior art and does not submit it during the non-provisional stage, that is another can of worms (like inequitable conduct and invalidity of the patent) but that comes after the patent issues, and involves litigation, which requires money. One of the patent examiner’s jobs is to perform a search, find prior art, and if material to patentability (rendering the invention not novel or obvious) the examiner will use it as a basis for a rejection.

In 2012 the USPTO received 542,815 utility patent applications and granted 253,155. There were 7,935 patent examiners at the USPTO in 2012. You do the math on that.

Third party preissuance submissions, also known as public prior art submissions, are a relatively new tool provided by Congress to reduce the load on the USPTO and provide a public instrument for fighting the propagation of patent trolls. 37 CFR § 1.290 establishes a new standard for prior art submissions and allows, for the first time, for the submitter to include a concise description of relevance of each document submitted. Previously that relevance was left up to the USPTO.

But the new third party prior art submission guidelines are also strict:

- If a submission is non-compliant it will be rejected and there is no delay incurred by the patent application

- If a submission is non-compliant you still lose the filing fees

- The submission must include a statement of relevance, indicating precisely how and where it teaches prior art

Submitting Art

When preparing a prior art submission, consider the numbers above for the USPTO workload. Each examiner, on average, reviews almost 70 patent applications per year. Time to review third party art submissions will be limited. Make it count.

- Make it clear what part of the invention claims are obvious. Don’t make the examiner guess.

- Include screen-shots that show explicitly where prior art renders the claims not novel or obvious.

- Remember, there is a difference between “novel” and “non-obvious”.

- Do a patent search yourself. If there are already identical claims elsewhere (even by the same inventor) include those references and quote the relevant portions.

- Know when to do it.

Timing

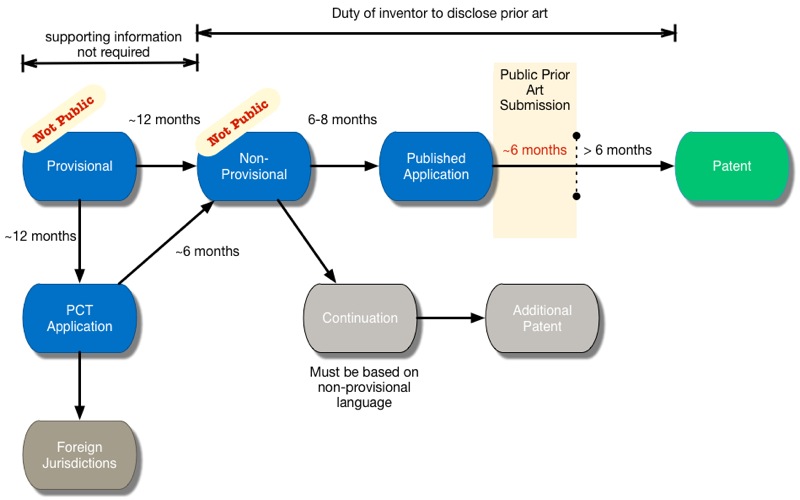

Typically the time allowed for public submission of prior art is 6 months after publication of the non provisional application, but there are circumstances which can change this time frame, such as if the first office action is mailed after the 6 month window (you have more time) or if the notice of allowance is mailed before the 6 month window (you have less time). However, this can change, if the USPTO responds with an office action before that time. It’s rare that the USPTO will allow an application before 6 months but it could happen if the applicant filed a request for prioritized examination. There are other ways to remove the window of public scrutiny on an application but they are rare enough that it’s not an issue for most applications.

Ask Patents has an excellent overview of what constitutes a meaningful prior art submission. Each person submitting prior art only gets 3 swings at the ball for free so it’s good to make it count and read the invention carefully. It also helps to understand what is prior art. If you have questions during the process, submit them to the Ask Patents forum.

There are no great ways to know when an application publishes other than to constantly search the USPTO system. However, the WIPO systems are considerably more friendly to the public’s desire for disclosure.6 In fact, you can even get an RSS feed for a query by author.

Applications Are Not Even Close to Patents

The weapon brandished by Oliver Reichenstein was an application for a patent. Swinging this around publicly to threaten developers to stay away from a feature is a bit like trying to rob a grocery store with the application form for a gun permit. It has no intrinsic value. If you have a checkbook, you can have a patent application.

An application for a patent is exactly that. It’s a request and about $300 to the USPTO. Under normal circumstances, this request is private. A provisional application has not been reviewed by the USPTO. A provisional does not include prior art but is simply a stake in the ground that sets an initial priority date. A priority date is the date used to establish the invention. Sometimes a patent filing date will become the priority date, but not always.

Typically once you file a US provisional patent application you have 1 year to further flesh out your invention and add additional data to the application. At the year deadline you may either abandon the provisional application or file a US non-provisional application claiming priority to the provisional.7 The non-provisional application is the application that is examined by the USPTO. It is at this point that a patent applicant has a duty to disclose known prior art to the USPTO.

This bears repeating: Patent applicants do not need to disclose known prior art to the USPTO until the provisional application is converted to a non-provisional application, which typically takes at least 1 year from the date of filing the provisional.

The patent application will become public upon publication within this 6-8 month period (about 18 months from the priority date or original filing date). This begins the narrow window for public submissions of prior art. And it is a very narrow window indeed. There will also be the inevitable period of back and forth discussion with the USPTO about the invention. In the vast majority of situations, the USPTO will initially deny an application, pending some additional information. All office actions are publicly available during this period of time.

Only when an application initially becomes public can you submit prior art against it. Even if, as in the iA Writer case, you have seen some aspect of the patent application or claims prior to the application being published by the USPTO, there is no need or use in submitting prior art. It’s not even possible.

However, when it publishes and becomes public, you will only have 6 months to do anything about it. This is why applicants typically are not foolish enough to show any detail of a patent application. It gives away the game plan and allows opponents to set their alarm clocks. By my clock, the public can submit prior art against application #61917358 in 18 months.

Here’s a not-so-simple flowchart of what it looks like for a patent application:

Abandonment

As outlined at the beginning, Information Architects have stated that they will not pursue their patent on Syntax Control. What does this mean?

Patent applications can not be canceled.8 They can be abandoned. The most common reason to do this is if you decide that the patent would not be worth the public disclosure of the invention.

There are a couple of ways to abandon a patent application:

- An applicant can simply abandon the process by inaction, and abandonment through non-action is free. It is basically a consequence of not communicating with the USPTO.

- An applicant can expressly abandon an application by formally filing paperwork with the USPTO. This costs money.

Both of these routes are still ambiguous since an applicant can file a continuation prior to abandonment of the original application. A continuation is basically a dependent application (a child) off of the original submission (the parent).

iA also had a previous patent application that has been erroneously claimed to be a patent by iA.

(Link to Tweet on December 27, 2013)

I say erroneously, because what they had was a patent application.

Let’s use this as an educational example.

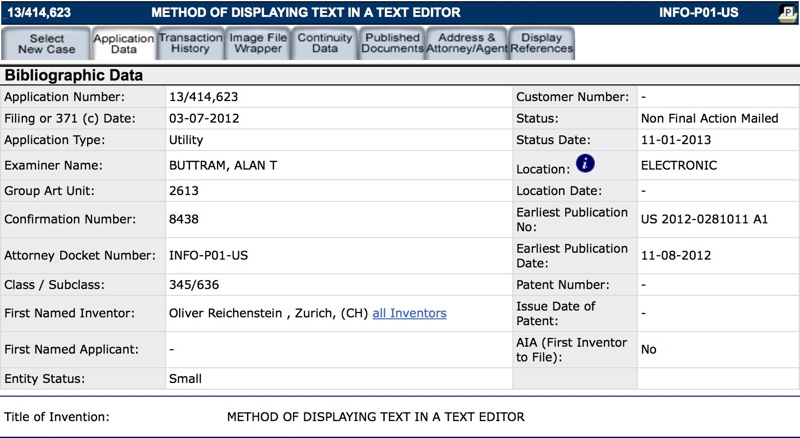

While there are several ways for the public to search and locate published patent applications, the easiest is to use the USPTO query by name. Once you have the application number, you can then use the USPTO Public Pair search to see the details.

This is what we see for application number 13414623, a previous application by iA:

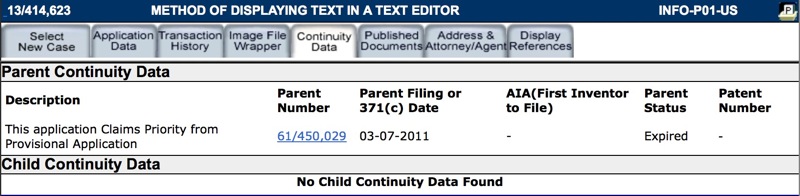

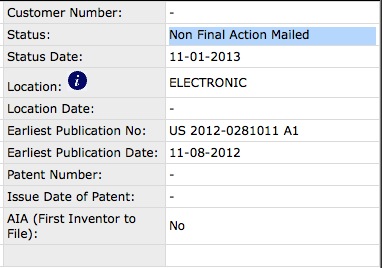

Looking at the provisional application date on the “Continuity Data” tab, we can see that it was applied for on March 7th 2011 (see below screen shot). On March 7th 2012 they properly filed a non-provisional (see above screen shot). On November 8th 2012 this application published and became public. This is still not a patent. It is simply a public disclosure.

Looking a little deeper we can see under the Continuity Data tab that this application states “No Child Continuity Data Found” which means that no other continuations were filed off of this non-provisional application. What you see is it. The patent status indicates that the provisional application has expired (which is normal).

Look back at the Application data tab under status. It says “Non Final Action Mailed”. This means that the USPTO requested additional information and/or rejected the application. It’s just the standard back and forth. This patent application is still very much alive and processing normally.

If Reichenstein takes no further action, the application will eventually go abandoned due to non-response to the office action. If there is an acceptance of his response and no further issues, the application may convert to a patent. Of course the back and forth could drag on for years too.

Conclusion and Effigies

iA (Oliver Reichenstein for all practical purposes) made several amateurish mistakes with perceived intellectual property. The first mistake would make most attorneys cringe. He attempted to leverage (or imply) a non-published patent application in an inappropriate way. Second, based on the public declarations on Twitter, they may have considered their patents “defensive” against patent trolls. However, these non-practicing entities produce no products and therefore can not be in violation of a patent, even if it did exist. In the end, I think there was an inappropriate perception that patents are practical tools to extract accolades:

(Link to Tweet on December 27, 2013)

Personally, I think iA fell victim to an over-powered ego but there is currently no definitive conclusion at this point.9 Unfortunately, stating that you will not exercise a patent, even publicly, does not limit you in the future. If the patent applications are not abandoned (explicitly or otherwise) then they may eventually become a patent and then it will be up to an entirely different process to determine if the Tweets are enforceable. However, at least for application number 61917358 filed December 18th, 2013 there may still be a 6 month period for public submission of prior art (if Reichenstein chooses to move forward with transitioning it to a non-provisional application by December 18th, 2014). If he takes no action then it will become abandoned.

For me this was an educational, if depressing, story. I learned three valuable lessons:

-

Suggestions of patents based on pending applications seems like a dangerous and irresponsible activity if you are simply proud of your work.

-

Since September 2012, the public has been able to submit prior art within a narrow window against a published patent application. If you are not using that system then you are not fighting against bad patents.

-

Understanding patents and the application process is vital to fighting the chilling effects caused by those that aim to abuse it, either through intention or ignorance.

-

Unless they have somehow hidden the fact through an elaborate shell or undisclosed association. Or if they are associated with Information Architects out of North Carolina. Given that there is no mention of that on their site, I’ll assume these are different corporate entities. ↩︎

-

I’ll focus on the USPTO. The USPTO process is similar enough to WIPO that I think it should be covered. ↩︎

-

While I believe that the patent system is necessary, I also believe it is fundamentally broken. I don’t agree with the fantastical idea that people will invent at the currently astounding rate we have today out of pure curiosity. Patents, copyright and trademark are some of the gears in the machinery of modern capitalism that enable the lifestyles we enjoy today. ↩︎

-

Unfortunately, what is considered temporary in one field, is eternal in a field like software. ↩︎

-

In other parts of the world, this is referred to as the inventive step, which immediately sounds more clear than “non-obvious”. ↩︎

-

Ironically, the iA claims to have designed the WIPO Web site and “information architecture”. ↩︎

-

or alternatively a PCT Application off of which a US non-provisional application may be later filed ↩︎

-

It’s not totally clear if iA understand that or not ↩︎

-

The arguments and defensives provided are so convoluted that it’s not entirely clear what the motivations were exactly. It’s not even clear that iA knows what a real patent is. ↩︎